Asie Visions - “New Southern Policy”, Korea’s Newfound Ambition in Search of Strategic Autonomy Asie.Visions, No. 118, January 2021

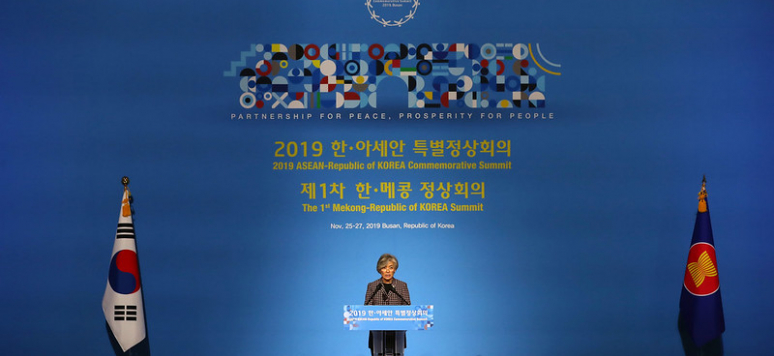

The New Southern Policy (NSP), the signature foreign policy initiative by President Moon Jae-in of the Republic of Korea (ROK) that was officially launched in November 2017, has opened a new chapter in Seoul’s relations with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) as well as India.

Since then, Seoul has adopted a whole-of-government approach that involved most of the ministries and government agencies in implementing the presidential agenda. The NSP as Seoul’s new regional strategy has been quite well-received by Southeast Asia and India, and successful in producing substantial deliverables over the last three years. To date, NSP remains the most successful and active foreign policy program under the Moon administration.

The NSP represents Seoul’s middle power ambition in search of greater strategic autonomy by taking on greater international responsibilities and roles that are deemed commensurate with its status and capabilities in global society. In this respect, Seoul has been endeavoring to diversify its external economic relations, reorient its diplomatic overtures toward Southeast Asia and beyond, and to promote active regional cooperation. However, Seoul’s middle power ambition has been significantly hampered by external geopolitical constraints as well as internal limitations of the NSP itself.

In an effort to minimize the risks of being drawn into the quagmire of US-China strategic rivalry, Seoul had to design the initiative as a purely functional cooperation agenda by setting aside sensitive strategic issues from the NSP’s “peace pillar”. By contrast, Seoul chose deliberately to prioritize development cooperation as the central domain of its NSP engagement in order to capitalize on its developmental experiences. As a consequence, this imbalance in the design of the NSP is crippling in that issues of regional security and strategic cooperation are largely absent from Seoul’s NSP drive. Also, Seoul’s cooperation with Washington’s Indo-Pacific strategy has been confined to a bilateral basis, and Seoul has engaged US only in those areas that are not politically sensitive such as development cooperation and non-traditional security.

For this reason, contrary to its self-imposed sense of responsibility to take greater regional roles as a robust middle power in the region, the space of Seoul’s expected activism under its ambitious NSP initiative has been effectively limited. Seoul needs to expand the “peace pillar” of its NSP beyond non-traditional security issues and take a more balanced and proactive stance in its engagement in regional strategic and security issues.