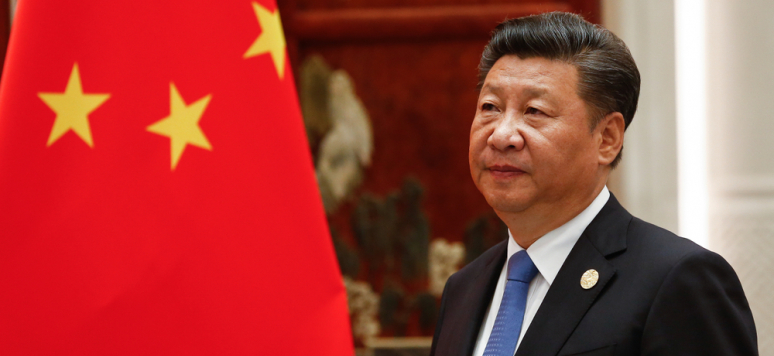

Publications hors Ifri - Xi Jinping’s Conquest of China’s National Security Apparatus "The Chinese Communist Party at 100", ISPI Dossier, 1 July 2021

One indisputable trend of Xi Jinping’s leadership since taking up the reins of government in 2012 has been the reaffirming of the Party’s control over the state, the army, society, and the economy. To this aim, establishing heightened control over the national security apparatus has been his means as much as an end. Xi has thus strengthened the Party’s overall security authority through major institutional and legal reforms.

A significant input of Xi’s governance is his concept of “national security” (guojia anquan 国家安全). On the 15th of November 2013, Xi penned an article [1] for Xinhua's official press agency wherein he exposed his vision of national security. He assessed that China faces a “double pressure”. The first pressure comes from the outside and threatens China’s core overseas interests as well as its national sovereignty and security. The second pressure comes from the home front and threatens both “political security” (zhengzhi anquan 政治安全) and “social stability” (shehui wending 社会稳定). This “double pressure”, Xi explained, requires a new comprehensive and centralized national security mechanism. It materialized a few weeks later, in January 2014, in the form of the “Central National Security Commission” (CNSC), placed under the CCP Central Committee and headed by Xi himself.

The All-Powerful CNSC

The CNSC became the highest organ supervising all kinds of foreign and domestic security issues, including economic, social, cultural, or ideological sources. Nonetheless, the core element that ought to be protected is the Party’s political security. This comprehensive approach to national security was later rubber-stamped by the National Security Law [2] that came into effect in July 2015.

First, the main consequence of this reform is that the CNSC decides what it considers a threat to national security (i.e., what is to be securitized), and second, that any behaviour or idea labelled as “threatening” to national security will be met with the harshest sentences.

The 2015 National Security Law is not unrelated to the Preservation of National Security Law in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region [3] (SAR), passed in Beijing on the 30th of June 2020. In fact, the latter is designed around Hong Kong’s context, while the former provides broad political principles. Nevertheless, the ultimate goal for both laws is to put national security under the control of the CCP. In addition, while the 2015 Law approved of the importance of the CNSC on national security matters, the 2020 Law established the Office for the Preservation of National Security in Hong Kong. This Office is under the direct supervision of the Central Government in Beijing and is “not subject to the jurisdiction of the Hong Kong SAR” (art. 60 [3]). Hence, through the CNSC, the CCP currently has complete discretion over what and who is a threat to national security in Hong Kong and can act directly in the SAR to stop newly recognized “criminals”, including political opponents and pro-democrats.

The harsh suppression of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang [4] also pertains to the CCP’s rationale for extreme control, including re-education campaigns and mandatory birth controls as well as the harassment of Uyghurs abroad.

Rule by Law

Xi has also been using legislative tools to impose and strengthen the levers of the CCP’s control. Since his rise to power, there has been a proliferation of security-related laws, for instance, on Counterintelligence (2014), Counterterrorism (2016), Cybersecurity (2017), National intelligence (2017) and Maritime police (2021). To this list the revision of the law around the People’s Armed Police (PAP) — which took effect in June 2020 — can also be added.

In June, the National People’s Congress passed the Law Against Foreign Sanctions, aiming to “protect national security and sovereignty [5]” (art. 1). It targets “individuals and organizations that directly or indirectly participate in the formulation, decision, and implementation of discriminatory restrictive measures” against China.

Tightening Control over the Armed Forces

Xi has also drastically strengthened the role of the CCP within the military and law enforcement as well as his leadership over it. In 2014, Xi established the Central Military Commission Leading Small Group for Deepening National Defense and Army Reform, which he headed. This Group oversees the broad reform of the armed forces and the “Central Military Commission” (CMC), the highest military organ of the “People’s Liberation Army” (PLA) – which is worth noting is the Party’s army, not the Republic’s. One decisive aspect of this reform that became effective in early 2016 is the shortening of the chain of command between the CMC and the armed forces themselves. The old and (overly) powerful four General Departments were dismantled to break their influence within the army and the CMC inherited their prerogatives. What is more, Xi also assigned himself a brand-new military title as Commander-in-Chief of the Joint Operational Command System. In addition to being the chair of the CMC, he is now also the operational commander, allowing him a tighter grip on the PLA.

The PAP is a paramilitary law enforcement agency designed for stability maintenance. It was previously under the dual supervision of the Ministry of Public Security and the CMC. However, after an additional reform in 2018, the PAP is now under the full authority of the CMC. During the same reform, the Chinese coast guard — which until then was under civilian rule — were merged into the PAP and placed under a military chain of command. In addition, the new Maritime Police Law now authorizes the de facto militarized coast guard to use lethal force at sea.

Enhancing the United Front Work

Finally, the Central United Front Work Department has also been significantly upgraded. This CCP institution under the Central Committee leadership directly links to the national security apparatus: most importantly, it is instrumental in protecting the CCP’s political security. Its goal is to expand the Party’s influence and fight against the CCP’s opponents at home and abroad. In 2018, its prerogatives were significantly extended, especially regarding the management of religious, ethnic, and overseas Chinese affairs — three issues that were previously dealt with by the state.

Deciphering the reform of the national security apparatus from 2012 to nowadays shows, first of all, how the CCP has strengthened its primacy over the state in terms of security governance, and secondly, how this process has served Xi in consolidating his grip on power. Now that presidential term limits no longer restrain Xi, it is more than likely that the CCP’s centrality and authority will grow even stronger after the 20th Party Congress in Autumn 2022.

This piece is part of the Dossier [6]"The Chinese Communist Party at 100" published by the Instituto Per Gli Studi Di Politica Internazionale (ISPI)

> Find the whole article on ISPI [7]'s website.