Lettre du Centre Asie - Democracy in Asia: Models, Trends and Geopolitical Implications Lettre du Centre Asie, No. 73, February 12, 2018

Assessing the state of democracy in Asia is a challenge. While some countries, such as Japan and India, have been showing the way from early days, some others, such as in Southeast Asia are still struggling to ensure stable and sustainable democratic institutions and practices.

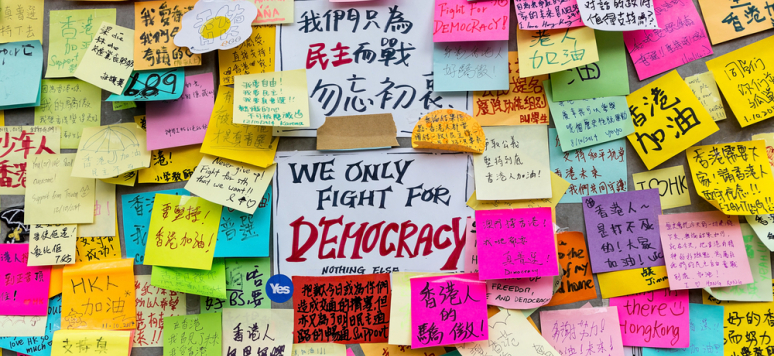

Several competing visions and approaches to democracy also coexist in Asia. The case of Hong Kong exemplifies the tensions and frictions between vibrant calls for liberal democracy and pushes to promote a more authoritarian political system.

This note offers the main conclusions of the discussions held during a conference at Ifri [1], on January 24, 2018.

Democracy and Foreign policy: Japan

The irruption of value-based diplomacy upholding liberal and democratic norms has been a distinctive trend in Asia since the mid-2000s. Japan, the oldest Asian democracy, and India, the largest one, have been two significant players in this regards, even if their democratic experiences and their approaches of international promotion of democracy are different.

Kaoru Iokibe (University of Tokyo) explained how unique Japan’s democratic experience and system are. If Japanese people have little sense of being a model, a number of Asian countries were actually inspired by Japan’s institutions. Nevertheless, there is often a lack of knowledge about Japanese specific, hybrid system that borrowed in part from the British model for its parliamentary system.

Despite this, the Japanese government has been actually quite proactive for more than ten years to uphold a foreign policy based on democratic and liberal values, which stresses implementing close partnerships with the other democracies in the region (trough the 2007 project of “Arc of Freedom and Prosperity”, for example). In particular, Japan reached out to Australia and India to build up strategic partnerships also aimed to form a network of “like-minded” partners around the core US-Japan alliance. More recently, Tokyo built up special relations with Paris and London, and, each time, the place of democratic and liberal norms is central. It is meant to support the current rule-based international order and offer an alternative to the revisionist powers that are challenging it.

Democracy and Foreign policy: India

India, for its part, is not in principle adopting an ideological approach in its diplomacy. In addition, many other identity factors are also informing Indian foreign policy. Nevertheless, as Zorawar Daulet Singh (CPR, New Delhi) explained, the rhetoric of democracy is used to legitimize strategic partnerships, and India joined the group of democracies that formed from the mid-2000s on.

This said, India is not ready to act as a crusader or a proselyte. If Delhi has reacted in the past to democracy crisis in its neighborhood, this type of interventions decreased in the post-Cold War period. India has indeed adopted a more pragmatic approach and is not going to intervene as long as its neighbors are committed to Indian security interests. As a result, the principle of non-interventionism still generally informs Indian foreign policy. For this reason, and because of the specific characteristics of Indian multiple political identities, the geopolitical Indian discourse on democracy should be interpreted with the domestic Indian context in mind.

Chinese culture and democratic values

According to Steve Tsang (SOAS, University of London), Confucian values that form the core of the Chinese cultural heritage, are not incompatible with democratic principles and practices. Confucianism, which states that the ruler should “do the right thing in the judgement of history”, has even been used as a support to the democratization process in Taiwan, for example. In Hong Kong, a democratic way of life, with individual rights, freedom of speech and rule of law found its way under the British rule. But this was not accompanied by democratic institutions, which explains in part the turmoil Hong Kong has been experiencing since 1997. In the People’s Republic of China, Confucian values, culture and traditions have been severely repressed in the Mao era, and therefore no longer have any real significance, role or impact in the current governance. This should be clearly acknowledged as the Chinese government has been recently instrumentalizing the traditional Confucian values to justify its decisions and actions. Right now, according to Steve Tsang, it is the Leninist system that is preventing the democratization of the country.

Southeast Asia: from democracy to stability

Sophie Boisseau du Rocher (Center for Asian Studies, Ifri) explained that the Southeast Asian political systems come from two influences: the European and American influence during the colonial period, with the imposition of a bureaucratic model of administration; and the Chinese political culture, based on status, hierarchy and loyalty.

While the democratic experiences of Southeast Asian countries are diverse, it can be said that democratization process did not follow a gradual, regular and straight line, but, on the contrary, underwent cyclical periods of progress and recess. Also, Southeast Asian countries defied the modernization theory stating that democratization would mechanically follow economic growth. Finally, several characteristics of the parliamentary democratic system, such as contradictory debate and power politics, were considered as running against traditional values of harmony, and democratic experiences has been often linked with instability. For that reason, as the late Singaporean leader Lee Kuan Yew stated, good governance was seen as quite different from a democratic government.

The 1997 economic crisis was seen as the result of the lack of democracy, transparency and check and balances, and led to efforts to favor democratization. However, since the beginning of the 2000s, a worrying trend toward illiberal democracy has struck most of the countries in Southeast Asia. The window of opportunity for democratization closed up because of two developments: first, in the wake of 9.1, in order to ensure a cooperation of ASEAN countries to fight terrorism, the US favored military interests at the expense of democratic forces. Second, the rise of the Chinese powerhouse demonstrated the efficiency of a system meddling political authoritarianism and economic growth. The growing relations with China also encouraged a number of Southeast Asian countries to evolve towards this kind of model.

No European model, no Asian model of democracy

The diversity of the democratic experiences is questioning the concept of “democracy” or “liberal democracy”. Ken Endo (Hokkaido University and Visiting scholar at Ifri) suggested that the reality of liberal democracy should be measured by the existence of “polyarchy”, that includes, as a minimum, an effective political participation and contestation.

Richard Youngs (Carnegie Europe) argued that there is no fundamental difference between European and Asian understanding of democracy, even if cultural and political variations of the concept do exist. The European model, once praised, no longer exists as democratic institutions and practices are increasingly under threat. Moreover, there is a pushback against the Western model of democracy. In this context, there is no very proactive policy from the EU to promote democracy in Asia. So far, in the strategic partnership the EU built with Asian countries, such as India or Japan, the democratic values are not meant to be the foundation of the relation.

The question of definitions is also at the core of the competition between political models, according to Alice Ekman (Center for Asian Studies, Ifri). Beijing, in recent years has been increasingly using key words commonly used by liberal democracies, but with different interpretations and meanings. This subtle practice is a way to reshape the global order, and is not always identified as such by other countries. This “definition gap” should then be addressed in order to clarify the terms of the debate. When taking about value-based diplomacy, the definition of “like-mindedness” should therefore be based upon a common understanding of key words and concepts, such as “rule of law”, “internet”, “culture”, “corruption” etc.