3374 publications

France has a new nuclear doctrine of ‘forward deterrence’ for Europe. What does it mean?

On Monday, French President Emmanuel Macron delivered a speech on France’s nuclear deterrence at the Île Longue naval base near Brest in Brittany, which hosts the country’s nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarines. Such addresses are a well-established presidential ritual, typically delivered once per presidential term and receiving moderate attention. This one, however, was highly anticipated in France and abroad, given the profound geopolitical shifts since Macron’s first nuclear speech in February 2020.

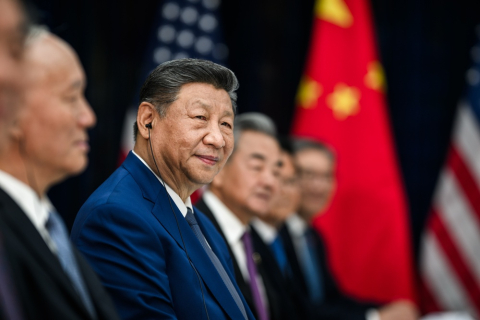

From Trump to Xi Jinping: Globalization's Great Rupture

The second Trump administration’s trade policy represents a rupture with the United States’ international commitments and a seismic shock for the multilateral trade system. Its destabilizing impact has been exacerbated by China’s disproportionate trade surplus, which has doubled since the 2020 pandemic. We are entering a new era marked by the erosion of norms and their replacement by a more transactional logic. For Europe, the challenge is enormous.

Germany: The Return of Military Service?

Abolished in 2011, conscription returned to Germany in 2025, albeit in a new, voluntary form. The decision in 2011 was broadly supported. Public opinion, like the political sphere, is more divided now. The reintroduction of voluntary service for men reflects the demands of the geopolitical landscape and the Bundeswehr’s need for troops. It remains to be seen whether the model chosen will fulfill the requirements of defense chiefs.

Digital Revolution, Economic Upheaval

The digital revolution is profoundly shaking up the economy, with the impact felt well beyond the digital sector itself. Indeed, it is transforming the very concept of value creation. Artificial intelligence represents a new phase that requires a colossal investment in physical infrastructure like data centers. Europe failed to grasp the scale of these changes in time, but it does have certain advantages.

Official Development Assistance in the Age of Deglobalization

Official development assistance has collapsed since 2023, both in Europe and in the United States. This decline has affected both developing and industrialized countries. Under fire in the Global North and South, the goals and methods of development assistance must be redefined if it is to adapt to an international landscape in which the principal actors—the United States, the European Union, China, the Arab countries—are adopting new stances.

The Global Economy: Caught in the Storm / Politique étrangère, Vol. 91, No. 1, 2026

The global economy has become the primary arena for the clash of power ambitions in a world where understanding, coordination, and concerted multilateralism seem to have been permanently marginalized. In this fragmented landscape, how will American and Chinese strategies interact? Will the European Union manage to break out of its decades-old framework in order to face new competition? And will it be able, like others, to integrate the announced shift from a production economy to a digital, information economy? And what role will financial institutions, and central banks in particular, play in this transitioning international economy?

Central Banks: Challenges and Tools in Geopolitical Rivalries

Central banks have become major strategic players in international economic balances. Faced with systemic crises (2008, Covid-19), the major central banks have developed unprecedented coordination of their interventions, fostering the emergence of the “Jackson Hole consensus.”

The 2026 State Elections in Baden-Württemberg: First Test For Chancellor Merz's Federal Government?

The state election in Baden-Wuerttemberg in March 2026 will be the first major test of public opinion for Chancellor Friedrich Merz's federal government. At the same time, Baden-Wuerttemberg is one of the federal states that—as an important location for the German automotive industry and its suppliers—is particularly affected by the transformation policy driven by climate change and the international conflict constellation.