Tanzania’s 2020 General Elections between Repression and Manipulation. A Consolidation of Magufuli’s “Authoritarian Turn”?

Tanzanian voters were called to the polls on Wednesday, October 28, 2020 to elect the country’s main political institution – the President, the National Assembly, and the District Councillors (diwani). Without surprise, the outcome of the sixth general elections since the reintroduction of multiparty politics in 1992 reaffirmed the longstanding grip on power of Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM).

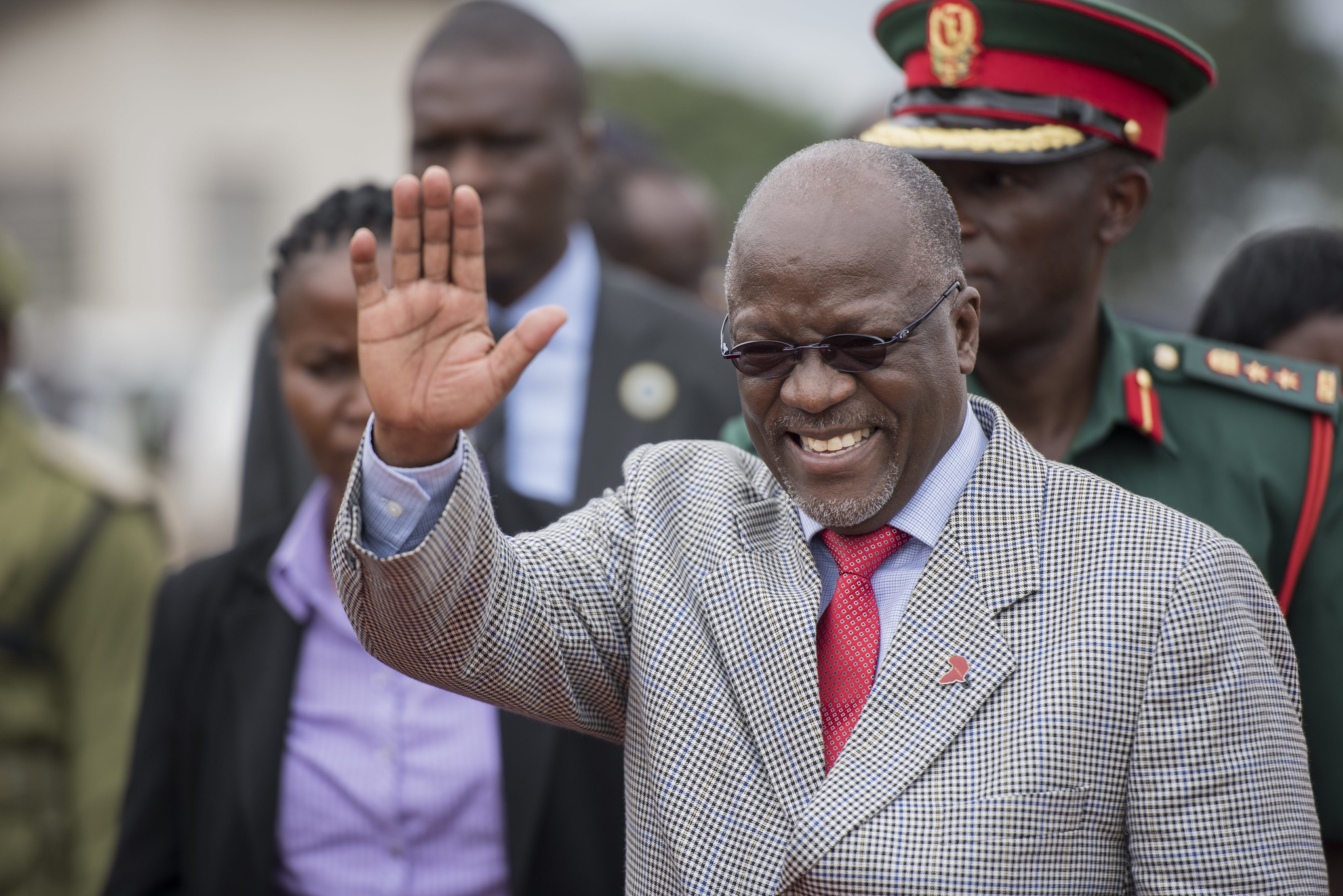

Althouth the electoral victory by the incumbent President John Pombe Magufuli and his party CCM was awaited, the results exceeded expectations about unfree and unfair elections and widespread fraud, as far as the ruling party claims to have “won” at least 225 out of 230 constituencies. CCM, formerly the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU), has been in power since Tanganyika’s Independence in 1961 and the subsequent formation of the United Republic of Tanzania in 1964. According to the results announced by the National Electoral Commission (NEC) on Friday, October 30 and contested by the opposition, its outgoing candidate John Pombe Magufuli has gathered 84% of the votes, compared to 58% in 2015. Even though the declaration of CCM’s victory was expected, the results lack credibility, and the level of irregularities,[1] violence and electoral manipulation estimated by experts and observers have led to international consternation and concern about Tanzania’s political trajectory.

In the midst of tense relationships with the international community, the elections were entirely domestically funded, and no non-African electoral observation was allowed this year. Local observation by civil society organizations was forbidden and several foreign media outlets were denied accreditation to cover the elections. However, the East African Community mission, under the leadership of former Burundi President Sylvestre Ntibantunganya declared the elections were free and fair, while the African Union mission, under the leadership of former Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan has not made any declaration yet.

The international hype around the Tanzanian “dictator”

In the past five years, civil society, media, and scholars dealing with Tanzanian politics have fed into a polarized debate about the country’s authoritarian “turn” led by its president. In power since 2015, Magufuli has built his reputation on his merciless governance style, including the limitation of democratic and human rights, policy-making based on economic nationalism and the spontaneous dismissal of high-level officials in the name of the fight against corruption and party loyalty. Although CCM’s success during elections has declined over the past 15 years (CCM won 62% of the votes in 2010 and 82% in 2005) with a historically low election result of 58% in 2015, Magufuli convinced voters with a political project based on the values of incorruptibility, integrity and rigor ,[2] aiming at serving the Tanzanian nation while putting the state administration back to work (with the slogan Hapa kazi tu!, “Here, we work!”). Whereas these initial political intentions were generally welcomed, the relationships with non-African bi- and multilateral partners quickly deteriorated.

Highly controversial measures, such as the restrictions of the freedom of expression and of assembly, political intimidation of opposition members, but also the denial of access to school for pregnant girls led traditional donors such as the Danish cooperation and the World Bank to temporarily withdraw from aid engagement. The business and investment climate in the country cooled off as an effect of protectionist economic measures, such as nationalizing key assets and access to resources, but also limiting work permits for foreigners and tightening local content policies.[3] Magufuli’s isolationist approach was again criticized during the COVID-19 pandemic. While his counterparts from the East African Community member countries were joining forces, the Tanzanian president undertook solo efforts: after denying the existence of the disease in Tanzania and declaring faith and religion as the main remedy against the coronavirus, Magufuli was accused by international community members of exposing his population arbitrarily to a serious health risk and further decreased his credibility as a responsible leader.[4]

Yet, despite the critical voices around Magufuli’s government, the president still received support and admiration for the stringency of his governance focusing almost exclusively on national issues. His investment in mega economic and infrastructure projects such as reviving the national airline Air Tanzania, building railway and power infrastructures and rehabilitating Dodoma as the Tanzanian capital but also by stressing the Tanzanian ownership over national resources (land, petrol, agricultural products, etc.)[5] are emphasized to defend his political legitimacy.

The hegemony of Tanzania’s ruling party since Independence

Magufuli’s governance style has often been analyzed as a “rupture” with and a “danger” to Tanzanian democracy. Despite the new level of democratic deficit reflected in the recent general elections, Magufuli’s first mandate can be considered as a new phase of a six-decade long authoritarian regime. In the first decade after Independence several decisions ended a short-lived but intense period of political pluralism[6]: the introduction of the single-party system in 1962, the repressive crackdown on dissent following the 1964 mutiny and the Arusha declaration of 1967 that inaugurated the socialist period. For the three following decades, the intense fusion of the State and the ruling-party and the continuous mobilization of the population in development projects deeply transformed Tanzanian political culture.[7] The subsequent liberalization period starting in the 1980s and the political transition of the 1990s were to a large extent controlled by CCM.[8] Party elite members reshaped the constitutional and legal architecture as well as the State apparatus and exploited neopatrimonial networks to their own benefit.

The perpetuating ‘de facto one party-State’[9] was consolidated through an electoral process designed to protect the hegemony of the ruling party. The president of the NEC is appointed by the President of the United Republic (who is at the same time the chairman of the ruling party). Returning officers at the district level, in charge of counting and announcing results are District Executive Directors (DED), themselves directly appointed by the President. Once presidential results are announced by the NEC, they cannot by law be challenged in court. Moreover, candidates of the ruling-party have enjoyed close relationships with security forces and civil servants that are crucial, especially at the local level, to gather information and intimidate opposition members. Finally, the first-past-the-post electoral system favors CCM, particularly at the presidential level; legal provisions make it difficult for the opposition to form and sustain a coalition; changes in electoral boundaries annihilate progress made by the opposition in their local implantation and limit their ability to challenge CCM’s majority at the National Assembly. Moreover, the opposition in Tanzania has always been subject to repression. In Zanzibar particularly, opposition members have experienced violent outbursts of State coercion since 1995, and particularly after the 2000 elections that led to 60 deaths, 300 injured and more than 2,000 departures in exile to Kenya. The rigging of the 2015 elections in the archipelago led to the dereliction of the 2010’s Government of National Unity agreement, that had eased the polarization of Zanzibari society along political lines).[10]

In other words, and despite the reintroduction of multiparty politics, the authoritarian structure of the State and its pervasive fusion with the ruling-party have continuously offered the tools necessary to CCM to maintain its hegemonic position. Consequently, Magufuli has not altered the nature of the regime during his presidency but has only been more straightforward and brutal in his use of the State apparatus to consolidate his position and repress dissent. On the mainland, the efforts of the opposition parties were met with more violent intimidation and repression than ever. Since 2016, the government has been banning political meetings, arresting and jailing opposition leaders under accusations of sedition, insulting the head of state or inciting mutiny. The pressure was also felt within the ruling-party as Magufuli, who was largely an outsider before 2015, strengthened his grip and marginalized internal dissenting factions.

Political competition leading to the 2020 general elections

Although CCM’s victory was expected by most, the electoral campaign revealed important political dynamics at stake. Despite the numerous attempts by the government and State bodies to repress and impede political organization, the main opposition parties raised their voices, formulated and articulated manifestos and toured the country, even though party meetings and rallies were cadenced by interruptions and interventions by security forces. As in 2015, the two main political opposition parties to CCM managed to form an electoral coalition and supported only one candidate for the presidential and constituencies’ elections, despite new constraining electoral regulations. Tundu Lissu, who barely survived an assassination attempt in July 2017, returned to Tanzania from exile in July 2020 and was endorsed as the presidential candidate for both Chadema and ACT-Wazalendo (ACT). In return, Chadema endorsed ACT’s runner for the Zanzibar’s presidential elections, sixth-time candidate Seif Sharif Hamad who had previously ran under the banner of the Civic United Front (CUF). Despite their initial divergences on economic policy, both Chadema and ACT insisted on the importance of democratic values and on their will to improve Tanzania’s relationships with international investors.

The pre-electoral climate was tense both on the archipelagoes and on the mainland. Opposition candidates were temporarily arrested, while security forces were accused of shooting people on Pemba Island (Zanzibar). Throughout the campaign, social media and especially Twitter were an important communication tool for opposition members and the intellectual diaspora to share views, express criticism and to hold online meetings. Yet, only a few days before the election day, the main telecommunication operators Airtime and Vodacom Tanzania reportedly shut down their services temporarily and text messages containing the names of opposition leaders were blocked.

Conclusion

The announcement of the election results by the NEC came as a shock, as opposition representatives lost their constituency one after the other. In a press conference held on Saturday, October 31, ACT and Chadema refused to recognize the results and called for peaceful protests starting on Monday, November 2.

Although the free and fair character of elections in Tanzania has always been questioned, the intensity and unscrupulousness of electoral manipulation observed before and during the 2020 elections is unprecedented and seems to inaugurate yet another phase and level of authoritarianism in Tanzania. The election results have wiped out the integral parliamentary opposition. They also form a clear message about internal dissent within CCM, enhance the politicization of State institutions and, most importantly, polarize the Tanzanian society. The long-term impacts of this episode are yet to be seen, but Magufuli, and maybe the entire CCM party, have made an unmistakable statement about their ruthless will to remain in power. Questions about a potential claim by Magufuli to change the Constitution, paving the way for his third mandate are getting louder. Yet, despite the outrage of the diaspora and critical scholars, the media coverage and reactions from international partners have been very mild until now.

[1]. Tanzania Elections Watch, “Preliminary Election Report”, 2020.

[2]. M.-A. Fouéré and C. Maingraud-Martinaud, “Une hégémonie compétitive contre vents et marées : les élections générales de 2015 en Tanzanie et à Zanzibar”, Politique africaine, 2015, Vol. 4, No. 140, pp. 145-163.

[3]. T. Jacob and R. H. Pedersen, “New Resource Nationalism? Continuity and Change in Tanzania’s Extractive Industries”, The Extractive Industries and Society, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 287-292.

[4]. F. Backman, “Communiquer avec l’aide de dieu : face au virus, les dix commandements du président tanzanien”, Fondation Jean Jaurès, 2020.

[5]. D. Paget, “Again, Making Tanzania Great: Magufuli’s Restorationist Developmental Nationalism”, Democratization, Vol. 27, No. 27, pp. 1240-1260.

[6]. J. Brennan, “The Short History of Political Opposition & Multi-Party Democracy in Tanganyika (1958-1964)“, in G. Maddox and J. Giblin (eds.), In Search of a Nation: Histories of Authority & Dissidence in Tanzania, Oxford: Ohio University Press, 2005, pp. 250-276.

[7]. D.-C. Martin, Tanzanie : l’invention d’une culture politique, Paris: Karthala, 1988.

[8]. G. Hyden, “Top-Down Democratization in Tanzania“, Journal of Democracy, Vol. 10, No. 4, 1999, pp. 142-155.

[9]. A. Makulilo, Tanzania: A De Facto One Party State?, Saarbrücken: Verlag Dr. Müller, 2008.

[10]. N. Minde, S. Roop and K. Tronvoll, “The Rise and Fall of the Government of National Unity in Zanzibar: A Critical Analysis of the 2015 Elections”, Journal of African Elections, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2018, pp. 163-184.

Download the full analysis

This page contains only a summary of our work. If you would like to have access to all the information from our research on the subject, you can download the full version in PDF format.

Tanzania’s 2020 General Elections between Repression and Manipulation. A Consolidation of Magufuli’s “Authoritarian Turn”?