A New Japan-France Strategic Partnership: A View from Tokyo

On the occasion of the conference held on the 22 November 2018 marking the 160th anniversary of Franco-Japanese diplomatic relations, Ifri publishes two parallel articles offering French and Japanese perspectives on the bilateral security partnership. Céline Pajon’s analysis of French point of view is available here.

The year 2018 marks the 160th anniversary of diplomatic relations between Japan and France. While Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s visit to Paris on Bastille Day had to be cancelled due to relief efforts following heavy rain and floods in the western part of Japan, he visited Paris on his way to an ASEM (Asia-Europe Meeting) summit in Brussels in October 2018 and met with President Emmanuel Macron. The two leaders reaffirmed, among other matters, their intention to strengthen security and defense cooperation between the two countries, including maritime security in the Indo-Pacific region.

This brief paper examines from a Japanese perspective opportunities and challenges facing the strategic partnership between Tokyo and Paris. There has already been remarkable progress in the fields of bilateral security and defense cooperation over the past several years. Seen from Japan, there are at least three major structural reasons why the value of France as a strategic partner for Japan has increased: Brexit, France as a “Pacific nation”, and increasing Franco-American cooperation. However, challenges remain for the relationship to flourish in a world of increasing uncertainty in the coming years and decades.

Deepening cooperation

While the political relationship between Japan and France has a long history, it was President François Hollande’s state visit to Japan in June 2013 that started a new and more substantial phase of strategic ties between the two countries.

The “exceptional partnership” (partenariat d’exception) was pronounced on that occasion, which led to the start of ministerial “2+2” meetings, bringing together the foreign and defense ministers of both sides, and defense equipment cooperation. Intelligence cooperation has also deepened particularly on Africa and the Middle East, as well as practical cooperation in Djibouti, where France has a traditionally strong presence and Japan maintains its first (and only) overseas facility in support of its counter-piracy operation in the Gulf of Aden. The two countries call each other “privileged partners” (partenaires privilégiés).

The conduct of joint military exercises involving the French armed forces and Japan’s Self-Defense Forces (SDF) has represented one of the most remarkable and visible developments in defense cooperation. A four-country joint exercise involving the two countries, as well as the United States and United Kingdom, took place in Guam and in the South Mariana Islands in May 2017. It included an amphibious exercise in which the French navy’s Mistral-class amphibious assault ship participated, in the context of the country’s deployment of the “Jeanne D’Arc” task force 2017. Paris also sent FS Vendémiaire, a frigate, to East Asia, including Japan, in 2018. In the meantime, Japan’s new maritime surveillance aircraft, P-1, participated in the Paris Air Show (SIAE) in June 2017 and visited France again in May 2018 for exchange.

In addition to dialogue and practical cooperation, including joint military exercises, Japan and France have also institutionalized their relations by signing an information security agreement in October 2011 and an agreement on defense equipment and technology transfer in March 2015. The two countries concluded in July 2018 an ACSA (acquisition and cross-servicing agreement) to facilitate cooperation, most notably joint exercises.

Japan and France have also been working closely together in addressing North Korea’s nuclear and ballistic missile development. Regarding sanctions against Pyongyang, the French role as a permanent member of the UN Security Council cannot be overlooked. Paris’s commitment to maintain UN sanctions and pursue CVID – complete, verifiable and irreversible dismantlement – was reiterated at the Macron-Abe meeting in October 2018. Maintaining common positions with France on those critical issues seems a significant diplomatic achievement for Tokyo, not least in the light of apparently decreasing commitment to UN sanctions by such countries as China and Russia, and South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s push to relax the sanctions.

Why France? (1) – Brexit

Beyond immediate issues, the first reason why the value of France as Japan’s strategic partner has increased recently and is set to increase in the coming years has to do with Brexit. Tokyo has long seen London as its primary partner in Europe. Not only have Japanese companies invested heavily in Britain as a gateway to the EU market, but also the government often relied on London as the principal interlocutor when dealing with EU matters. Put simply, Brexit means that Tokyo will lose Britain as its gateway to the EU both in economic and political terms.

Even after Brexit, the UK as a country will remain a major player on the world stage, and the Japan-UK bilateral relationship in various fields, most notably security and defense, will continue irrespective of Brexit. Furthermore, it seems clear that London now needs non-European partners more than ever before – which led to its overture to Tokyo, including sending ships and troops to Japan for joint exercises.

However, it is inevitable that London can no longer be Tokyo’s main gateway to Europe once it leaves the EU. This requires that Tokyo find an alternative gateway to the EU. In this regard, France and Germany are the two biggest and most obvious candidates to replace Britain. While the importance of Germany as the largest economy in the EU can hardly be dismissed, when it comes to security and defense cooperation, Paris has always been more active than Berlin.

Why France? (2) – France as an Indo-Pacific Country

When President Hollande labelled France as a “Pacific nation” in his address to the Japanese Diet in June 2013, not many Japanese were immediately convinced. Nevertheless, the fact that France possesses a vast exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and, more importantly, 1.5 million of its citizens in the Indo-Pacific region makes it a resident power in the region. France keeps a permanent military presence in such places as New Caledonia, with a total of 7,000 troops in the entire Indo-Pacific region.

Being a resident power in the Indo-Pacific nation means that France is an engaged security actor there and is physically exposed to China’s increasing activities – including military – particularly in the South Pacific. France sent five ships to the Asia-Pacific region in 2017 and is becoming increasingly vocal in expressing concerns about China’s assertive and expansionist behavior, not least in the South China Sea. French Armed Forces Minister Florence Parly said that “Just because you plant your flag somewhere doesn't mean that territory changes hands”, and Paris conducts its own freedom-of-navigation operations in the South China Sea. Tokyo firmly supports and appreciates Paris’s increasing engagement in the region.

President Emmanuel Macron’s idea of the “Indo-Pacific axis” between France, India and Australia, referred to in his speech in Sydney in May 2018, can also be seen as complementary to Abe’s vision of the “free and open Indo-Pacific (FOIP)”. Macron even talks of the need to maintain balance against hegemony, while not directly referring to China. Tokyo has also strengthened security and defense ties with Canberra over the past decade, including in the context of US-Japan-Australia trilateral cooperation. There are more possibilities for those bilateral, trilateral and so-called minilateral cooperation to enhance synergy for security and prosperity in the wider Indo-Pacific region.

Why France? (3)— France as a close ally of the US

Third, France’s deepening security and defense cooperation with the United States, including joint military operations across the world, also makes it a more attractive (and easier) strategic partner for Japan. It is often argued that one of the major reasons why the UK is always considered as the primary partner and easiest to cooperate with for Japan in Europe stems from the fact that the UK is believed to be the closest US ally in Europe.

The French armed forces are now fighting together with American forces in the global coalition against the Islamic State (IS) in Syria and Iraq, and close logistical and other cooperation is taking place in Africa as well. Counter-terrorist cooperation between France and the US has deepened, particularly since the terrorist attacks in Paris in November 2015 which killed 130 people. This has also led to deeper intelligence cooperation between the two countries.

Macron is the leader who has the closest personal relationship with Trump in Europe, despite all the policy differences, not least on the Iranian nuclear deal and climate change. This statement holds true, even if the extent to which the personal relationship with President Donald Trump can be translated in concrete policy achievement is increasingly questionable. The nature of Macron and Abe’s personal relationships with Trump may be different, but the French and Japanese leaders share a relief in the importance of embracing Trump as closest as possible in personal terms. This constitutes yet another foundation for the two countries to develop cooperation.

Resource constraint

For the Japan-France strategic partnership to flourish, an obvious question concerns the assets and resources each country can bring to the table. Japan looks increasingly busy in addressing challenges in the immediate neighborhood, namely North Korea and China. As a result, there are growing voices arguing that the country should concentrate its defense assets and resources on the most urgent challenges, rather than investing in global engagement, which is thought to be less important, despite the political discourse of a “proactive contribution to peace” and FOIP advanced by Abe.

Furthermore, assuming that Tokyo expects Paris to engage more in Asian security, it needs to be prepared and willing to reciprocate by committing to European security in view of Russia and other challenges. Certainly, it is not in Japan’s interest to be seen as a demandeur – expecting France to be engaged in Asia, while showing unwillingness to contribute to European security. For France as well, despite its growing military engagement in the Indo-Pacific region, it is hardly easy to find the necessary assets and resources given its commitment in other parts of the world, most notably Africa and the Middle East as well as Europe.

One way to mitigate this assets and resources constraint in the maritime domain would be to make full use of what is already available. For example, Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Force sends a training squadron to Europe once every two years – led by a training ship(s), but always accompanied by a destroyer (DD). Also, Japan assigns a ship to counter-piracy in the Gulf of Aden, rotating every six months. On the French side, in addition to its permanent naval presence in New Caledonia, it often deploys ships and submarines to the Indian Ocean for operations and exercises. It is imperative for Tokyo and Paris to share information about their respective ship deployments, so that the two countries can conduct more joint exercises without them costing too much. This is already beginning to take place, but more could be done.

Overcoming stereotypes

Another challenge has to do with perceptions. Particularly notable on the Japanese side is the stereotyped perception that France is always inclined to be anti-American and soft on China. Memories of France’s vehement opposition to the US-led Iraq War remain fresh, supplemented by its role in trying to lift the EU’s arms embargo on China in the mid-2000s. As a result, the value and reliability of France as Japan’s reliable strategic partner has consistently been questioned. However, the reality has changed substantially. As argued above, the level of France’s military cooperation with the US is currently at an unprecedented level, and perceptions of China have deteriorated sharply in Paris -- something of which not many Japanese are fully aware. It is in France’s interest to try to raise Japanese awareness of these new realities.

On the other hand, observers see Tokyo as too close (or worse, subservient) to the US, and its relationship with China as overly conflictual. Here again, the reality is much more nuanced. It is therefore in Japan’s interest to highlight Japan’s own security and defense efforts, as well as the fact that the Japan-China relationship has always been deep, and has improved in recent years.

It is clear, then, that Japanese-French cooperation can benefit both themselves and the wider world – particularly in these ever more conflictual and uncertain times. It is high time to make this partnership truly exceptional.

Download the full analysis

This page contains only a summary of our work. If you would like to have access to all the information from our research on the subject, you can download the full version in PDF format.

A New Japan-France Strategic Partnership: A View from Tokyo

Related centers and programs

Discover our other research centers and programsFind out more

Discover all our analysesEuropean Union-India: Lasting Rapprochement or Partnership of Convenience?

The partnership between the European Union (EU) and India has long been limited to economic exchanges. Its political dimension has gradually developed, culminating in its elevation to the status of a “strategic partnership” in 2004. However, the failure of negotiations for a free-trade agreement in 2013 slowed this momentum. Since the early 2020s, in an uncertain geopolitical context, bilateral rapprochement has gained new momentum.

Japan’s Takaichi Landslide: A New Face of Power

Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi has turned her exceptional popularity into a historic political victory. The snap elections of February 8 delivered an overwhelming majority for the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), driven by strong support from young voters, drawn to her iconoclastic and dynamic image, and from conservative voters reassured by her vision of national assertiveness. This popularity lays the foundation for an ambitious strategy on both the domestic and international fronts.

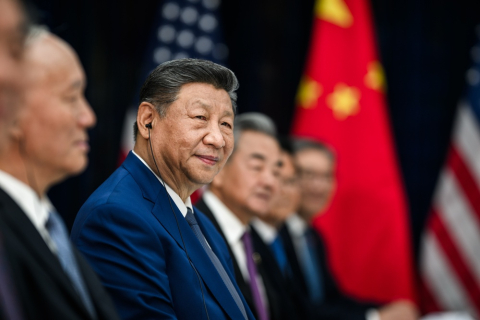

The U.S. Policy Toward Taiwan Beyond Donald Trump: Mapping the American Stakeholders of U.S.-Taiwan Relations

Donald Trump’s return to the White House reintroduced acute uncertainty into the security commitment of the United States (U.S.) to Taiwan. Unlike President Joe Biden, who repeatedly stated the determination to defend Taiwan, President Trump refrains from commenting on the hypothetical U.S. response in the context of a cross-Strait crisis.

China’s Strategy Toward Pacific Island countries: Countering Taiwan and Western Influence

Over the past decade, China has deployed a diplomatic strategy toward the Pacific Island Countries (PICs). This strategy pursues two main objectives: countering Taiwan's diplomatic influence in the region and countering the influence of liberal democracies in what Beijing refers to as the "Global South."