The Contradictory Impacts of Western Sanctions on Economic Relations between Russia and Sub-Saharan Africa

How does Russia maintain economic ties with Africa despite Western sanctions? An analysis of investments, trade, and the circumvention strategies deployed by Moscow.

Titre

Key Takeaways

Since 2010, economic relations between Russia and Sub-Saharan Africa have experienced renewed momentum. This revival has resulted in modest trade, with a structural surplus in Russia’s favor, and investments in the mining and hydrocarbon extractive sectors.

While Western economic sanctions have hampered the expansion of Russian investment in Sub-Saharan Africa and affected trade, Russian-African dialogue on economic cooperation continues, focusing on the energy sector.

This paradox can be explained by political factors, the most important of which is the African desire not to align itself with the Western-promoted policy of isolating Russia.

The strategic lesson of this paradox is that economic sanctions must be accompanied by political discourse, aimed not only at the sanctioned regimes or public opinion in the sanctioning countries, but also at third countries. Currently, such a discourse appears to be seriously lacking.

Titre Edito

The economic dimension of “RussAfrica”

The economic dimension of “RussAfrica”

While Africa recently moved from last to sixth place in the ranking of the 10 priorities of the Russian Foreign Policy Concept, the revival of Russian-African economic exchanges actually dates back to the years 2010-2012, after two decades of limited exchanges following the collapse of the Soviet Union (USSR). In 2021, trade reached $22 billion and included sales of arms, refined petroleum products, fertilizers and manufactured goods. This limited exchange had the advantage of being a surplus for Russian trade, as arms sales accounted for the bulk of Russian-African trade (Russia at the time held 40% to 50% of the African market).

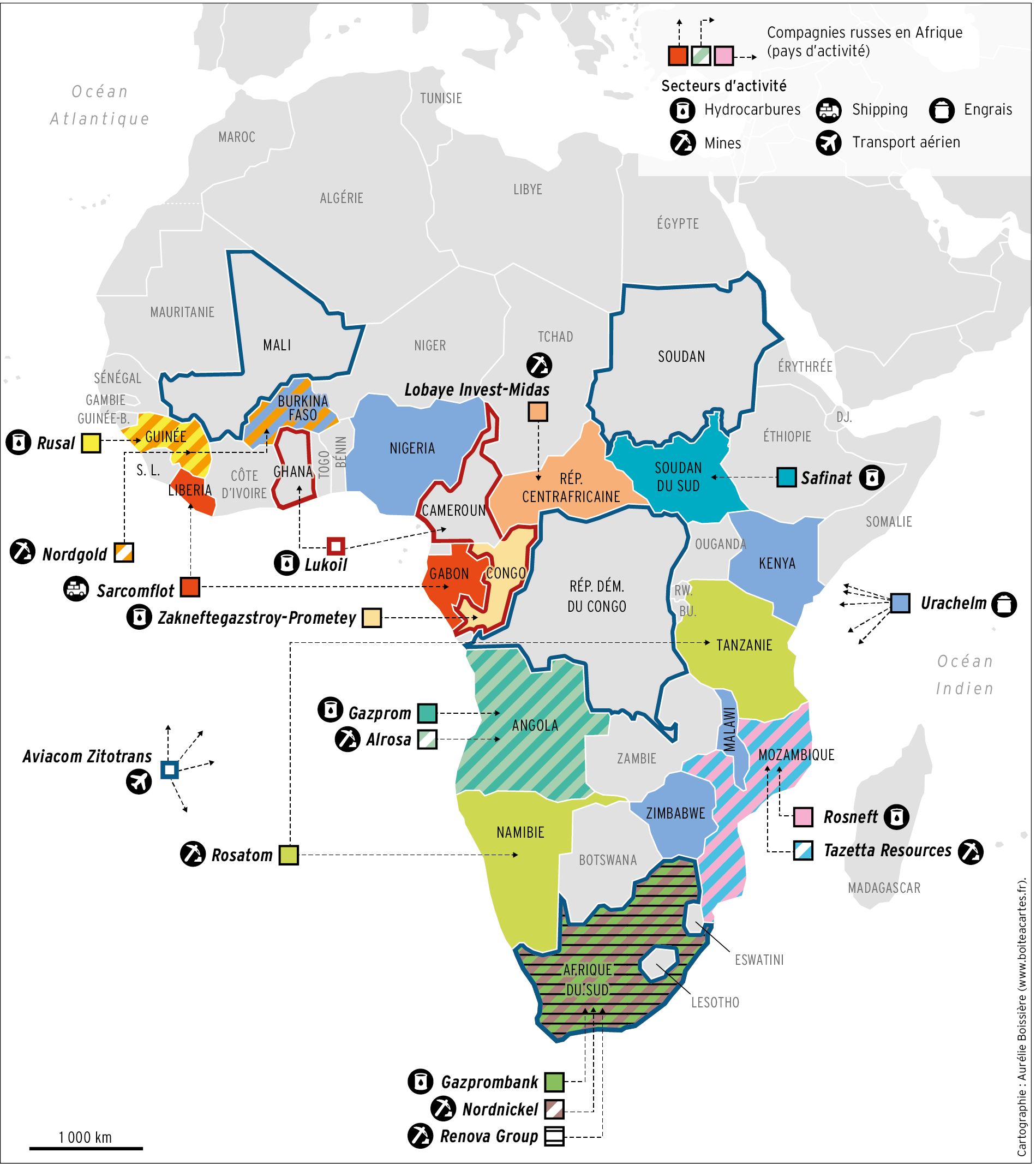

In addition, Russian extractive companies were looking for opportunities on the continent and beginning to invest there. Major Russian oil companies were present in Africa’s main production region, the Gulf of Guinea, and signaled their interest in the newly discovered gas fields of Mozambique. Russian mining companies were investing in Southern Africa, in particular. The most expensive project was signed in 2014 in Zimbabwe. The Great Dyke Investment was a partnership between a Russian consortium (Vi Holdings, Rostec, and Vnesheconombank) and a Zimbabwean company, Landela Mining Venture, to develop one of the world’s largest platinum deposits, at an estimated cost of $3 billion. Furthermore, the world’s leading diamond producer, the Russian company Alrosa, became the second-largest shareholder in the Catoca diamond mine in Angola in 2018.

The revival of Russian-African economic exchanges actually dates back to the years 2010-2012

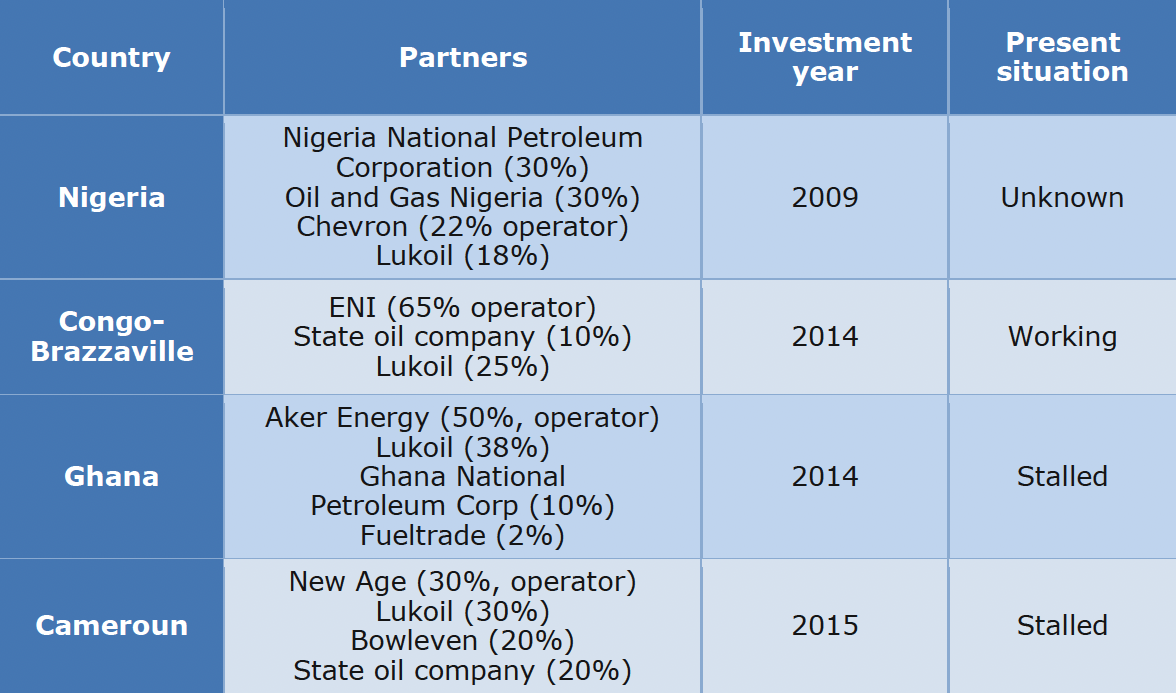

During the past decade, Russian companies Lukoil and Rosneft have entered the upstream hydrocarbon production sector in partnership with Western companies acting as operators. Among Russian hydrocarbon companies, Lukoil has made the largest investments in Africa, for an amount between one and two billion dollars. It has acquired stakes in the development of several projects in the Gulf of Guinea. Its most expensive acquisition was an $800 million stake in the development of the Marine XII concession, off the Congolese coast. ENI is the operator of this gas field, in which Lukoil is a 25% partner. Similarly, Lukoil has partnered with companies in Ghana (Pecan field), Cameroon (Etinde field) and Nigeria. In 2019, Rosneft also signed a memorandum with the National Hydrocarbons Company of Mozambique to develop natural gas fields in this country, where it had won a tender in 2015. Russian companies had also signed contracts for oil infrastructural projects (refineries, pipelines, etc.), particularly in Nigeria, South Sudan and Uganda.

However, the expansion of Russian companies in sub-Saharan Africa has also suffered setbacks. Rosneft’s chairman, former Russian Deputy Prime Minister Igor Sechin, a close associate of Putin, tried, unsuccessfully, to acquire stakes in Angola and Gabon. Gazprom failed to enter the Mozambican offshore gas sector, and Lukoil’s ambitions in the new Senegalese offshore production area were thwarted. In 2020, the Australian company Woodside Energy successfully prevented Lukoil from joining the consortium operating the Sangomar offshore field. In Mozambique, the Russian state-owned bank VTB Capital was implicated in the major hidden debt scandal that erupted in 2016. This scandal sparked tensions between the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Mozambican regime and led to the arrest of the finance minister. Overall, the revival of economic relations did not enable Russia to catch up with China and the European Union in Sub-Saharan Africa, where it remained a negligible trading partner and investor.

Russian mining, oil, and gas investments have also been a strategic tool that connected oligarchs with African leaders. For example, Viktor Vekselberg, the head of the Renova Group (a multi-sector company founded in 1990), invested in a financial company linked to the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa’s second-largest manganese mine. He also donated $826,000 to the ANC. The hidden financial relations between the South African ruling party and this oligarch then sparked a heated political controversy.

In the landscape of Russian-African economic relations, Yango, the “Russian Uber”, represents a two-fold exception. On the one hand, this company, which began expanding into Africa in 2018 and is now present in 13 African countries, is part of the tertiary, not industrial, sector. It offers passenger transport and delivery services in Africa, Europe and Asia. On the other hand, unlike many companies in the Russian extractive sector, its Chief Executive Officer, Arkady Volozh, who has lived in Israel since 2014, was not affiliated with the Russian regime. After being sanctioned by the European Union (EU) in 2022, Arkady Volozh was rehabilitated in 2024.

Titre Edito

The impact of Western sanctions

The impact of Western sanctions

Before the outbreak of war in Ukraine in 2022, Russia had a portfolio of projects in African extractive sectors and a modest but structurally positive trade surplus with Sub-Saharan Africa. But Western economic sanctions have shifted the balance. Doing business with Russian companies has become both more complicated and more expensive, particularly in the hydrocarbons sector.

Sanctions have hampered the expansion of Russian investments. Deprived of the financing necessary for their expansion abroad, Russian extractive companies have had to adopt withdrawal strategies that vary depending on the investor. Some firms have formally withdrawn, others have suspended their partnerships, and the last category of companies have kept their assets but reduced their operations and ambitions. Finally, some of their Western and African partners have terminated their partnerships with Russian companies.

As early as 2022, Vi Holdings, a Russian international investment group, announced that it was abandoning the Great Dyke Investment. Similarly, two Russian companies abandoned their projects in South Africa. At the end of 2023, Nornickel sold its stake in the Nkomati mine in South Africa to its local partner African Rainbow Minerals. At the beginning of 2025, the South African government confirmed that it was seeking an alternative financier to Gazprombank, which had been chosen in 2023 to finance the revival of the Mossel Bay gas refinery. In Angola, in 2024, the government announced the end of a long-standing partnership with Alrosa, notably in the development of the Catoca diamond mine.

As in the mining sector, Russian investments in the hydrocarbons sector have been thwarted or even blocked. In Cameroon, the offshore project needs a new partner to ensure development. The Franco-British company Perenco, which had considered buying New Age’s shares and becoming its operator, reversed its decision in 2023, deeming a partnership with Lukoil too risky. In Ghana, following rumors of a sale of Lukoil’s shares, the Norwegian operator Aker recently withdrew from the project and sold its shares to a Nigerian company. Only the liquefied natural gas (LNG) production project carried out in partnership with ENI in Congo-Brazzaville is progressing well.

While it is easy to determine whether or not hydrocarbon projects are developing, it is more complicated to assess the evolution of trade relations between Russia and sub-Saharan Africa. As in the case of other sanctioned countries (Iran, North Korea, etc.), economic sanctions against Russia have led the authorities to opt for “economic secrecy”. Statistics are no longer published, and trade and business relations are hidden. However, it appears that arms sales have declined, and the export of refined petroleum products has increased.

Russia has gained market share in the refined petroleum products sector

Western sanctions have had a paradoxical effect on oil trade between Sub-Saharan Africa and Russia. On the one hand, by capping the price of Russian oil, Russia has gained market share in the refined petroleum products sector. Many tankers from the ghost fleet have been supplying ports in West and East Africa on behalf of new trading companies that have emerged in Dubai since 2022. Cheap Russian oil benefits not only the Asian market but also the African market. On the other hand, as previously mentioned, Russian oil companies have been forced to disinvest from some African projects.

Unlike Russian oil, Russia’s cheap wheat policy had only a limited effect in sub-Saharan Africa, where Russia mainly exported fertilizers until 2022. At the last Russian-African summit in 2023, Vladimir Putin announced free provision of wheat and fertilizers to friendly regimes, which was carried out in 2024. While the free wheat shipments were intended for six countries (Somalia, Mali, Burkina Faso, Central African Republic, Eritrea, and Zimbabwe) , the free fertilizer shipments were sent to southern African countries (Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe).

Africa is probably Russia’s largest gold supplier

The biggest mystery in Russian-African trade is gold, which plays an important role in Russian monetary strategy. Although it is difficult to estimate volumes, Africa is probably Russia’s largest gold supplier. Russian gold import networks consist of official companies, such as NordGold operating in Guinea and Burkina Faso, and mafia-like paramilitary organizations, such as the Wagner Group, which operates several gold mines in the Central African Republic. Before the outbreak of war in Sudan, the Wagner Group was involved in gold trafficking, thanks to its alliance with General Hemedti’s rebel forces, who control gold-mining areas. But in Sudan and Burkina Faso, ongoing conflicts have significantly impacted gold mining. NordGold had to close its Taparko mine for security reasons in 2022, while international sanctions forced this company to change refiners and conceal its exports through intermediaries.

Whether it is oil or gold, one country plays a central role in Russian-African trade: the United Arab Emirates (UAE). This country hosts many Russian front companies and is one of the main trading centers for gold. The teams of Litasco, Lukoil’s trading company, quickly relocated from Switzerland to the UAE in 2022, while most of the new trading companies suspected of selling Russian oil are based in Dubai. Although it denies it, the UAE has played and continues to play an important role in circumventing the economic sanctions imposed against Russia. In response to pressure on the Emirati authorities, the accounts of several front companies have been closed, but others continue to operate.

Whether it is oil or gold, one country plays a central role in Russian-African trade: the United Arab Emirates (UAE). This country hosts many Russian front companies and is one of the main trading centers for gold. The teams of Litasco, Lukoil’s trading company, quickly relocated from Switzerland to the UAE in 2022, while most of the new trading companies suspected of selling Russian oil are based in Dubai. Although it denies it, the UAE has played and continues to play an important role in circumventing the economic sanctions imposed against Russia. In response to pressure on the Emirati authorities, the accounts of several front companies have been closed, but others continue to operate. Thus, NordGold’s gold refining, which was relocated from Switzerland to Dubai, is now carried out by a Turkey-based refiner owned by the Turkish subsidiary of an Emirati bank. While the UAE is trying to be more discreet, it has not renounced its role as a broker for Russian trade.

Titre Edito

Maintaining the illusion of economic partnership

Maintaining the illusion of economic partnership

In sub-Saharan Africa, the effects of economic sanctions against Russia have been mixed. While Russian companies’ investment policy on the continent has been hampered, Russian-African trade continues, and discussions on economic cooperation between Moscow and African governments are ongoing. Russian-African trade is suffering primarily from the decline in Russian arms exports, due to the conflict with Ukraine.

Paradoxically, while Russia’s investment portfolio in Africa has contracted since 2022, Russian-African dialogue on economic projects continues. For example, a Tanzania-Russia business forum was held in Dar-es-Salaam in October 2024. Similarly, the governments of Nigeria and Kenya have discussed plans for Uralchem to establish fertilizer plants. In 2024, an agreement to construct a pipeline in Congo-Brazzaville and an agreement to build a refinery in South Sudan were concluded with Moscow. African presidents continue to send requests for economic aid to Moscow (Central African Republic, Guinea-Bissau, Equatorial Guinea, etc.), while Rusal is considering a major infrastructure project (port and railway) to connect friendly regimes in the Alliance of Sahel States to the Atlantic, via Guinea-Bissau.

At the same time, Alrosa is considering opening mines in Zimbabwe, while NordGold has just obtained a new gold concession in Burkina Faso, and Rosatom plans to build small nuclear power plants in several African countries. Most of the major economic cooperation projects put forward by Moscow in Africa concern the energy sector, the point of convergence of African demand and Russian expertise. But this economic cooperation for large energy infrastructure projects is more apparent than real, due to a lack of sufficient financial capacity.

Russia wants to project the image of a major economic power

The ongoing dialogue on economic partnership reflects a convergence that is more political than economic. For the Russian government, it is about projecting the image of a major economic power capable of exporting its expertise, sharing it with poor nations under the yoke of the “collective West”, and demonstrating the failure of the latter’s policy of political and economic isolation. Moscow, therefore, maintains “economic dialogue” with African governments to promote its political image, thanks to various organizations created specifically for this purpose. In July 2024, the Chamber of Commerce and Investment for Africa, Russia & Eurasia was inaugurated in Dakar in the presence of Mikhail Bogdanov, Special Representative of the Russian President for the Middle East and Africa, and Yassine Fall, Senegal’s Minister of African Integration and Foreign Affairs. According to Senegalese diplomacy, this organization aims to strengthen “the strategic partnership between Russia and Africa [...] across a wide range of key sectors such as the economy, trade, security, agriculture, energy, industry, and transport”. For their part, African governments have at least four motives to engage with Moscow on an illusory economic cooperation: a historical Russophilia, the absence of alternatives, the success of Russian propaganda, and the desire not to align themselves with the policy of isolating Russia promoted by the Europeans.

While some African leaders are fooled by Moscow’s claims, others lack donors and have no alternatives (Eritrea, Guinea-Bissau, South Sudan, Equatorial Guinea, etc.). In addition, many African governments do not want to participate in the strategy of isolating Russia promoted by the EU. This diplomatic approach stems from several rationales. Rising tensions between major powers and the multi-dependency in which many African countries find themselves encourage neutrality. But it may also involve asserting greater distance from Europe through a different diplomatic stance. The four reasons to engage with Moscow are not mutually exclusive. Thus, the government of Congo-Brazzaville has been signing agreements with Moscow, probably for all four reasons simultaneously. Conversely, the new Senegalese government, which is currently the focus of the Kremlin’s attention in Africa, is above all concerned with distancing itself from European diplomacy.

Titre Edito

Conclusion

Conclusion

The revival of economic relations between Russia and sub-Saharan Africa from 2010 to 2012 resulted in modest trade, albeit structurally a surplus for Moscow, as well as Russian investments in the African mining, oil and gas sectors. Although limited, these exchanges had a strategic dimension, insofar as they concerned sectors such as arms and energy, and involved key players in both the Russian and African regimes.

Western economic sanctions against Russia affected Russian-African economic relations in contradictory ways. They reduced investments by major Russian extractive companies on the continent and forced Russian-African trade into the economic underground. At the same time, they allowed Moscow to increase its sales of refined petroleum products, and importantly, this did not lead to a breakdown in dialogue on economic cooperation. The continuation of dialogue is certainly misrepresented by Moscow as proof of the ineffectiveness of economic sanctions, but it is rich in lessons about the behavior of third countries. Economic sanctions against a country like Russia are not enough; they must be accompanied by a political discourse with third countries, a discourse that is seriously lacking.

Available in:

Themes and regions

ISBN / ISSN

Share

Download the full analysis

This page contains only a summary of our work. If you would like to have access to all the information from our research on the subject, you can download the full version in PDF format.

The Contradictory Impacts of Western Sanctions on Economic Relations between Russia and Sub-Saharan Africa

Related centers and programs

Discover our other research centers and programsFind out more

Discover all our analysesGabon: Has an — Almost — Exemplary Transition Produced a New Political Model?

In two rounds of voting, on September 27 and October 11, 2025, the citizens of Gabon elected the members of both their local councils and the new national assembly. This marked almost the final stage of political transition, little more than two years after the coup d’état that had overthrown the more than five decades old dynastic regime of the Bongos — Omar, the father, who died in office in 2009, and then his son Ali, who is now in exile.

Claiming "The People": Youth Booms, Ailing Authoritarians and "Populist" Politics in Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania

This study analyses the emergence of so-called “populist” political tendencies in three East African countries: Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. It builds its analysis on a wider discussion of the term “populism”, its use and applicability in (eastern) African settings before going on to examine the drivers of three cases of populism: William Ruto’s 2022 election victory in Kenya and the “Hustler Nation”; Bobi Wine’s opposition to Yoweri Museveni in Uganda; and John Magufuli highly personal style of government in Tanzania.

The Revenue Sources Sustaining Sudan’s Civil War. Lessons for the year 2023

Wars require money and resources, and often, most conflicts involve controlling sources of income and supply lines or denying them to enemies. This has been the case in Sudan’s past conflicts and is again as the civil war—between the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF), commanded by General Abdelfattah al-Burhan, and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), commanded by General Mohammed Hamdan Daglo “Hemedti” —has sunk into a protracted conflict.

Anglo-Kenyan Relations (1920-2024) : Conflict, Alliance and a Redemptive Arc

This article provides an evidentiary basis for postcolonial policy in its analysis of Anglo-Kenyan relations in a decolonization era.