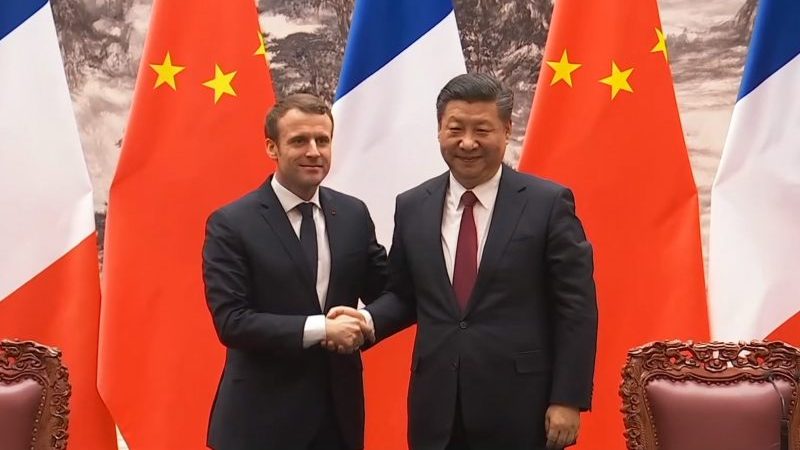

A Rough Year Ahead for the China-France Strategic Partnership

2020 has been a challenging year for the world economy. Although the magnitude of the shock triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic differed widely from one country to another, no economy was left unscathed.

China, where the virus originated, was the first country to be hit (with a sharp contraction of close to 7 percent of its Gross domestic product (GDP) in the first quarter of 2020) but it is also the first (and almost the only) economy which managed to technically avoid a recession (typically defined as two consecutive quarters of economic decline). Indeed, Chinese economic growth bounced back very quickly and returned to positive territory in the following three quarters. As a result, China is one of the few economies (together with Taiwan and Vietnam) which experienced positive growth in 2020.

Thanks to these outstanding performances, Beijing undoubtedly feels vindicated in asserting the superiority of the Chinese model and is becoming increasingly self-confident. Interestingly, although the Belt and Road Initiative, Xi’s signature project, has been running into trouble over the past year or so, China has managed to turn things around to its advantage even on this point.

For the rest of the world economy, and France is no exception, 2020 has not been challenging exclusively from an economic point of view. The crisis has also strained the bilateral relation with China. Paradoxically, the crisis has brought China and the European Union (EU) (and France for that matter) closer together (through mutual assistance in the context of the pandemic) and pushed them further apart at the same time as China’s assertiveness, and even aggressiveness, was increasingly directed against its western partners. In an unprecedented move, France’s foreign minister had to summon the Chinese ambassador to France in mid-April after the embassy published on its website a sharp and ill-founded criticism of the country’s handling of the coronavirus crisis.

A More Clear-Eyed Strategy in 2021?

With a number of important events and celebrations coming up in the year ahead (approval of the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-25) at the National People’s Congress in the spring, 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party in July), China can be expected to maintain its assertive stance. In other words, the so-called wolf warrior diplomacy has now become a clear feature of China’s behavior on the global stage. These new conditions call for a change in approach on the part of its partners.

In response to China’s rising aggressiveness, public opinion on China has become increasingly negative in France. As reflected in a recent survey conducted in mid-2020 (in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis), overall, the French public is decisively negative about China, with 62 percent of those polled having a negative or very negative opinion, while only 16 percent have a positive or very positive view of China. More importantly perhaps, for a large majority of those surveyed, this negative feeling has worsened over the past three years. The position of the French public on the question of human rights is particularly clear: among the respondents, 74 percent consider the human rights situation in China as ranging from “somewhat bad” to “very bad”.

This perception dovetails to a large extent with that of the government. Over the past year or so France’s approach on China has been shifting away from a low-profile attitude (some may have called naivety) towards more firmness. But until now this had not always been translated into clear policy actions. President Macron’s ambivalent (even ambiguous) stance vis-à-vis China, which sometimes left his partners perplexed, is likely to change in the present context, with more firmness both in rhetoric and actions.

However, talking tougher to China does not mean that China’s cooperation will not also be sought on issues of mutual interest. More specifically China’s support is needed in order to effectively respond to a broad range of key global issues close to Paris’ heart, such as the Paris agreement on climate change, but also the preservation of biodiversity, World Trade Organization (WTO) reform and the like. A good example of such cooperation is the post-COVID-19 Debt Service Suspension Initiative launched by the G20 in the spring of 2020 to which China brought its active support. Seeking for cooperation should not be seen as a sign of weakness but as sheer pragmatism.

Aligning France’s and EU partners’ interests

An important tenet of France’s China strategy has traditionally been to seek to form a united front within the EU. First, on some policies such as trade, the exclusive competence lies with the EU, and not with the individual Member States. Secondly, on other issues, given the differences in size between France and China a better approach is for France to team up with the other EU Member States to have more weight in negotiations with China. On this specific point, the convergence of views with Germany has tended to deepen over the past few years. More specifically, the German industry’s position has shifted since the highly publicized acquisition of Kuka robotics by China’s Midea in 2016 towards more caution vis-à-vis China. Although this change of attitude is not always very clear (as exemplified in the relatively hasty push to conclude the “Comprehensive Agreement on Investment” with China in late December, right before the end of the German rotating presidency of the EU) German politics has also shifted toward a harder stance on China, and it is likely that Chancellor Angela Merkel’s successor will take up a different line on relations with Beijing. However, getting the Franco-German engine running is no longer enough and getting a broader EU consensus is more important than ever.

To be sure, the EU has shown more determination to face up to China in 2020, with several concrete measures taken such as the new guidelines and temporary rules on financial take-over by non-EU actors or the White Book on foreign subsidies. France is likely to go on pushing for a coordinated (at least as much as possible) European approach on China. But getting all EU member states’ interests consistently aligned on the China issue will undoubtedly be a daunting task.

> The complete article is available online on the ISPI website.

Related centers and programs

Discover our other research centers and programsFind out more

Discover all our analysesEuropean Union-India: Lasting Rapprochement or Partnership of Convenience?

The partnership between the European Union (EU) and India has long been limited to economic exchanges. Its political dimension has gradually developed, culminating in its elevation to the status of a “strategic partnership” in 2004. However, the failure of negotiations for a free-trade agreement in 2013 slowed this momentum. Since the early 2020s, in an uncertain geopolitical context, bilateral rapprochement has gained new momentum.

Japan’s Takaichi Landslide: A New Face of Power

Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi has turned her exceptional popularity into a historic political victory. The snap elections of February 8 delivered an overwhelming majority for the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), driven by strong support from young voters, drawn to her iconoclastic and dynamic image, and from conservative voters reassured by her vision of national assertiveness. This popularity lays the foundation for an ambitious strategy on both the domestic and international fronts.

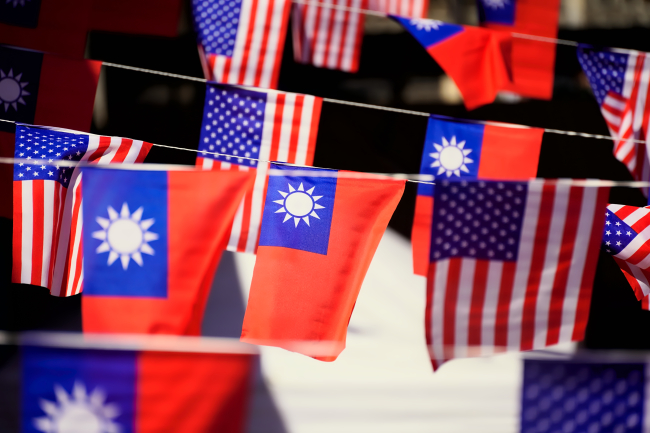

The U.S. Policy Toward Taiwan Beyond Donald Trump: Mapping the American Stakeholders of U.S.-Taiwan Relations

Donald Trump’s return to the White House reintroduced acute uncertainty into the security commitment of the United States (U.S.) to Taiwan. Unlike President Joe Biden, who repeatedly stated the determination to defend Taiwan, President Trump refrains from commenting on the hypothetical U.S. response in the context of a cross-Strait crisis.

China’s Strategy Toward Pacific Island countries: Countering Taiwan and Western Influence

Over the past decade, China has deployed a diplomatic strategy toward the Pacific Island Countries (PICs). This strategy pursues two main objectives: countering Taiwan's diplomatic influence in the region and countering the influence of liberal democracies in what Beijing refers to as the "Global South."