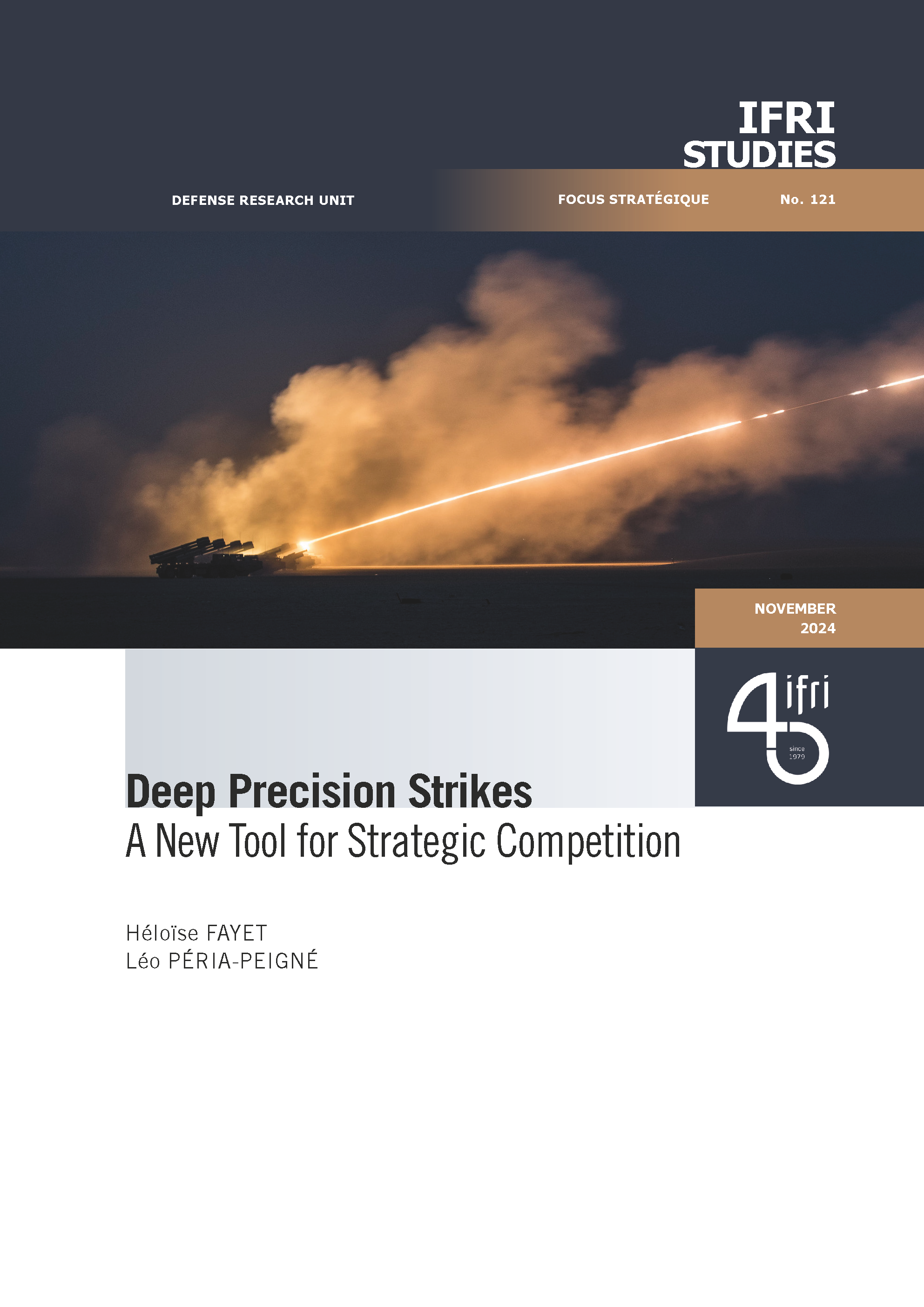

Deep Precision Strikes: A New Tool for Strategic Competition?

Reaching deep into the enemy’s system to weaken it and facilitate the achievement of operational or strategic objectives is a key goal for armed forces. What capabilities are required to conduct deep strikes in the dual context of high-intensity conflict and strengthened enemy defenses?

A strategic differential

Since the winter of 2023, the stalemate on the Ukrainian front has prompted the belligerents to make greater use of deep precision strikes, in search of a military effect that has become impossible to achieve on the front line. Conventional ballistic and cruise missiles are being used jointly with drones and increasingly varied guided munitions, capable of exploiting gaps in the enemy’s defenses and attacking different types of high-value targets. This intensive use of deep strikes has made European nations aware not only of their vulnerability to these threats but also of the limits of their own capabilities in this area. Little used since the end of the Cold War, Europe’s deep-strike capabilities appear limited, relying for the most part on high-performance air-to-ground delivery systems, which have nevertheless been acquired in limited quantities. The ground-to-ground capabilities of European armies have often been reduced to the remnants of systems mostly inherited from the Cold War.

Developed during the First World War as a means of overcoming the blockage of the front line, deep strikes use matured and diversified throughout the twentieth century as long-range bombers, and later rockets and long-range missiles, were improved. From the 1960s onward, deep strikes were closely linked to nuclear issues, but nevertheless retained an important conventional dimension. The end of the Cold War and of the prospect of a high-intensity peer conflict reduced the use of these capabilities, in the absence of a front line capable of determining the depth to be struck. This became a global issue with the successive demonstrations of force by US forces, capable of striking all around the globe at very short notice.

Dissemination in all theaters of conflict

Technological efforts continue unabated, however, with various programs aimed at improving the speed, accuracy, and stealth of deep-strike effectors. Other theaters are also seeing the development of major deep-strike arsenals. China, for example, is developing capabilities to interdict US forces on its regional approaches, including the development of very long-range delivery systems capable of threatening US bases in Japan, the Philippines, and beyond. In response, the United States, but also smaller players such as South Korea, are acquiring and deploying weapons capable of posing a significant threat in the theater. The autonomous development of long-range strike capabilities is also an integral part of the regional strategy of Iran and its proxies vis-à-vis Israel, as well as its potential regional competitors.

After decades of gradual erosion in the international regulation of these deep-strike capabilities, Europe is seeing Russian systems evolve at great speed in the wake of the conflict in Ukraine. Missile salvos are enriched by long-range UAVs, multiplying the flight profiles and complicating the task of air defense on both sides. Relatively simple to manufacture and less costly than modern cruise missiles, these delivery systems could be used by non-state actors, as the Houthis in Yemen are already doing, and pose a significant threat to European armed forces whose current defenses are primarily designed for threats at the top end of the spectrum. The conflict in Ukraine therefore raises questions not only about Europe’s deep-strike capabilities but also about its ability to defend itself against such threats.

What model for France?

France’s capabilities in this area are solid but limited. The French Air and Space Force and the French Navy can rely on the SCALP (Système de croisière conventionnel autonome à longue portée) and MdCN (Missile de croisière naval) cruise missiles, which are set to be upgraded with more powerful delivery systems by the end of the decade. However, these munitions have been acquired in limited quantities due to a lack of resources, and some of the acquired SCALPs have been sold to Ukraine. The French Army, for its part, now has only a handful of rocket launchers, which are due to be withdrawn from service in 2027. Moreover, the ground forces lack the long-range ammunition found in the inventories of other armies in Europe and cannot fire beyond 80 km. As the conflict in Ukraine has highlighted the need for a longer-range capability to tackle a more spread-out and dispersed adversary, the replacement of these systems should mark a move upmarket to 150 km and beyond for a French land capability that has been rather neglected since the end of the Cold War, due to a lack of need and budgets. Developing a longer-range land fire capability should also enable France to meet its NATO obligations within the framework of an autonomous French army corps, especially as the development of a very deep-strike capability, beyond 1,000 km, is being studied within a multinational European framework. Naval and air capabilities are also benefiting from programs to develop faster, more maneuverable, or stealthier delivery systems, carried out in cooperation with the United Kingdom.

At a time when international competition is becoming increasingly aggressive and uncompromising, deep-strike capabilities are playing a more important role, forcing all players to take an interest in them or risk being put in a vulnerable position, from both an offensive and defensive point of view.

Available in:

Themes and regions

ISBN / ISSN

Share

Download the full analysis

This page contains only a summary of our work. If you would like to have access to all the information from our research on the subject, you can download the full version in PDF format.

Deep Precision Strikes: A New Tool for Strategic Competition?

Related centers and programs

Discover our other research centers and programsFind out more

Discover all our analysesFrance has a new nuclear doctrine of ‘forward deterrence’ for Europe. What does it mean?

On Monday, French President Emmanuel Macron delivered a speech on France’s nuclear deterrence at the Île Longue naval base near Brest in Brittany, which hosts the country’s nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarines. Such addresses are a well-established presidential ritual, typically delivered once per presidential term and receiving moderate attention. This one, however, was highly anticipated in France and abroad, given the profound geopolitical shifts since Macron’s first nuclear speech in February 2020.

Bundeswehr: From Zeitenwende (historic turning point) to Epochenbruch (epochal shift)

The Zeitenwende (historic turning point) announced by Olaf Scholz on February 27, 2022, is shifting into high gear. Financially supported by the March 2025 reform of Germany’s “debt break” and backed by a broad political and societal consensus to strengthen and modernize the Bundeswehr, Germany's military capabilities are set to rapidly increase over the coming years. Expected to assume a central role in the defense of the European continent in the context of changing transatlantic relations, Berlin’s military-political position on the continent is being radically transformed.

Main Battle Tank: Obsolescence or Renaissance?

Since February 2022, Russian and Ukrainian forces combined have lost more than 5,000 battle tanks, a much higher volume than all the European armor combined. Spearhead of the Soviet doctrine from which the two belligerents came, tanks were deployed in large numbers from the first day and proved to be a prime target for UAVs that became more numerous and efficient over the months. The large number of UAV strike videos against tanks has also led a certain number of observers to conclude, once again, that armor is obsolete on a modern battlefield. This approach must, however, be nuanced by a deeper study of the losses and their origin, UAVs rarely being the sole origin of the loss itself, often caused by a combination of factors such as mines, artillery or other anti-tank weapons.

Mapping the MilTech War: Eight Lessons from Ukraine’s Battlefield

This report maps out the evolution of key technologies that have emerged or developed in the last 4 years of the war in Ukraine. Its goal is to derive the lessons the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) could learn to strengthen its defensive capabilities and prepare for modern war, which is large-scale and conventional in nature.